Material Matters: Brass

Brass roosters. [Image source]

Used for everything from jewelry to hose couplings, musical instruments, locks, and electric sockets, brass is not only versatile in use, but also notably appealing in appearance with its warm, golden glow. Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, and changing the percentages of each element changes the properties of the brass. It's often confused with its cousin, bronze, an alloy of copper and tin. In the world of CNC machining, brass 360, otherwise known as free-machining brass, is the brass of choice for milling, boasting the highest machinability among all the copper alloys.

Although the earliest form of brass dates back to Neolithic times and brass is a common alloy today, it only became widely used in the field of engineering in the last millennium. We've all heard of the Copper Age, followed by the Bronze Age and the Iron Age, but there was never a Brass Age. Why? Brass wasn't easy or inexpensive to make because zinc wasn't easy to make, and native zinc had to be used. As a result, for most applications, bronze was used instead since tin was readily available.

The earliest known instances of brass, dating back as early as 500 B.C., are thought to be “natural alloys,” made from smelting zinc-rich copper ores. Roughly 2,000 years ago, the Greeks and Romans started melting calamine ore, which contains both copper and zinc. The zinc dispersed throughout the copper, and brass was made. The Romans famously used it for their golden helmets and other ornamentation.

Brass was (and still is) also used to make parts for precision instruments like clocks, watches, chronometers, and marine navigation devices because of its durability and corrosion resistance. In 1738, British metallurgist William Champion filed a patent for his accessible technique of making zinc from calamine and charcoal. And in 1832, British industrialist and metal roller George Frederick Muntz invented 60/40 brass (60% copper and 40% zinc), enabling the production of inexpensive, workable brass plates.

History

Brass astrolabe manufactured by the workshop of Geiorg Hartmann in Nuremberg in 1537

Although the earliest form of brass dates back to Neolithic times and brass is a common alloy today, it only became widely used in the field of engineering in the last millennium. We've all heard of the Copper Age, followed by the Bronze Age and the Iron Age, but there was never a Brass Age. Why? Brass wasn't easy or inexpensive to make because zinc wasn't easy to make, and native zinc had to be used. As a result, for most applications, bronze was used instead since tin was readily available.

The earliest known instances of brass, dating back as early as 500 B.C., are thought to be “natural alloys,” made from smelting zinc-rich copper ores. Roughly 2,000 years ago, the Greeks and Romans started melting calamine ore, which contains both copper and zinc. The zinc dispersed throughout the copper, and brass was made. The Romans famously used it for their golden helmets and other ornamentation.

Brass was (and still is) also used to make parts for precision instruments like clocks, watches, chronometers, and marine navigation devices because of its durability and corrosion resistance. In 1738, British metallurgist William Champion filed a patent for his accessible technique of making zinc from calamine and charcoal. And in 1832, British industrialist and metal roller George Frederick Muntz invented 60/40 brass (60% copper and 40% zinc), enabling the production of inexpensive, workable brass plates.

Properties

Less expensive than pure copper and more malleable than bronze or zinc, brass has countless applications because of its many useful properties. How malleable the brass is has everything to do with its zinc content. Brass with more than 45% zinc is actually not workable, whether hot or cold. Workable brass generally has less than 40% zinc.

Highly malleable and workable

Low melting point

Corrosion resistant

Low friction

Durable

Conductive (electric and thermal)

Susceptible to stress cracks

Non-ferromagnetic

Antibacterial qualities (due to copper content)

Specifications

Density: 0.303 to 0.315 lb/cu in (8.4 to 8.73 g/cm3)

Brinell Hardness: 55 – 73

Tensile strength: 58,000 psi

Melting point: 1,650 to 1,720 °F (900 to 940 °C), depending on composition

Specific heat capacity: 0.0896 – 0.0908 BTU/lb-°F (0.375 – 0.380 J/g-°C)

Electrical resistivity: 0.00000318 – 0.0000280 ohm-cm

Machinability rating: 20 – 106%

[Source MatWeb]

Brass Alloys

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements, one of which must be a metal, and there are a wide variety of brass alloys, each with different properties. Here are some of the most common:

Brass 360 (free-machining brass): The most common brass alloy consists of 61.5% copper, 35.5% zinc, and 3% lead. Boasting the highest machinability rating of all copper alloys, brass 360 is a dream to machine. This alloy is used for plumbing products, couplings, electrical components, circuit boards, and industrial hardware, among a host of other applications. When we machine brass using our Bantam Tools milling machines, this is our alloy of choice.

Nordic gold: Used to make coins in a number of different currencies (including the 10, 20, and 50-cent euro coins), this alloy is revered for its gold color and antimicrobial and tarnish-resistant properties. Nordic gold is made of 89% copper, 5% zinc, 5% aluminum, and 1% tin.

Gilding metal: Made of 95% copper and 5% zinc, this is the softest of the alloys, most commonly used for ammunition bullet shell casings.

Pinchbeck: Invented around 1730 by London-based maker of clocks and watches Christopher Pinchbeck, this alloy is known for its close resemblance to gold at a time when nothing less than 18-karat gold was available. This alloy was made with either 93% copper and 7% zinc or 89% copper and 11% zinc. Nowadays, either 14-karat gold or gold plating is used rather than pinchbeck brass.

Muntz metal: Named after the man who patented this alloy (also called the 60/40 brass or “yellow metal”) originally used as a replacement for the copper sheathing on the bottom of boats. Made of 60% copper, 40% zinc, and a trace amount of iron, this alloy offers the benefits of copper for marine applications for a fraction of the price.

Uses

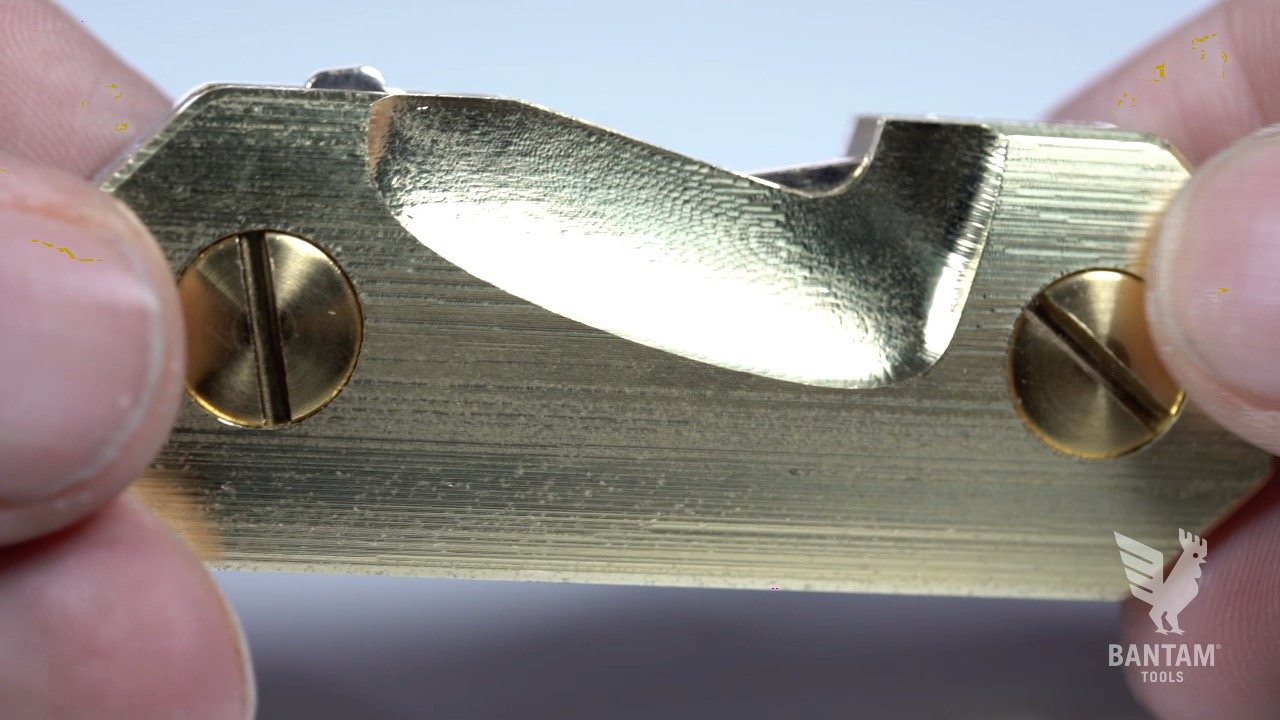

The numerous properties of brass make it useful in many applications. For example, its corrosion resistance and low friction make brass a go-to choice for locks, hinges, gears, bearings, zippers, plumbing, hose couplings, valves, and electrical plugs and sockets. Because of its copper content, brass is antimicrobial, making it ideal for medical applications and bathroom fixtures.

Musical instruments: The malleability of brass, along with its durability, workability, corrosion resistance, and acoustic properties make it prime for musical instruments including trumpets, tubas, trombones, cymbals, gongs, and bells, as well as components of electric guitars and violins. There’s a reason why an entire part of an orchestra is called “the brass section”! Fun fact: The very first brass instrument was a trumpet, dating back to around 1500 B.C.!

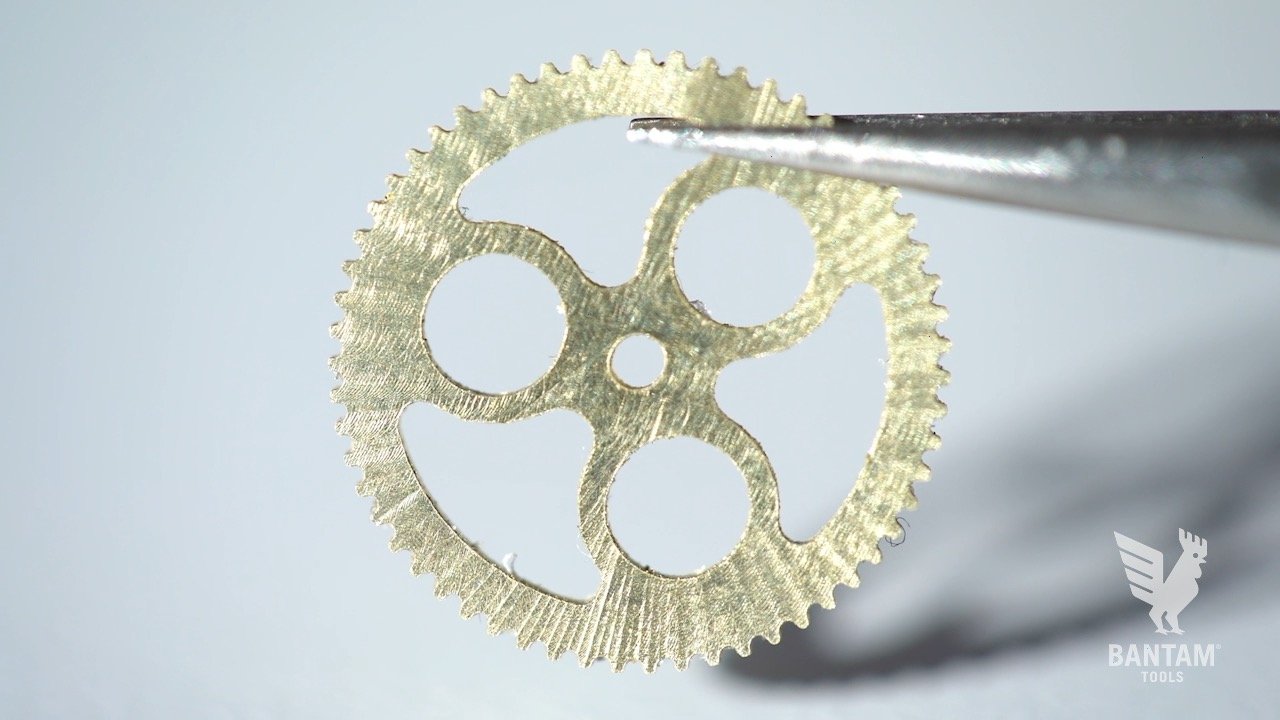

Precision instruments: The workability of brass, combined with its durability and low friction explain why it’s such a great material for precision parts for watches, compasses, astrolabes, chronometers, and barometers. Brass is used to make everything from intricate gears to clock hands and etched faces.

Antimicrobial applications: Brass’s resistance to bacteria is one of the main reasons it’s been so useful in both marine and medical applications. On ships, it’s long been used to prevent “biofouling,” or the accumulation of living matter like algae, plants, and microorganisms. In the field of medicine, hospitals employ brass in touch surfaces to avoid bacterial transmissions, and it’s also used in a number of medical devices.

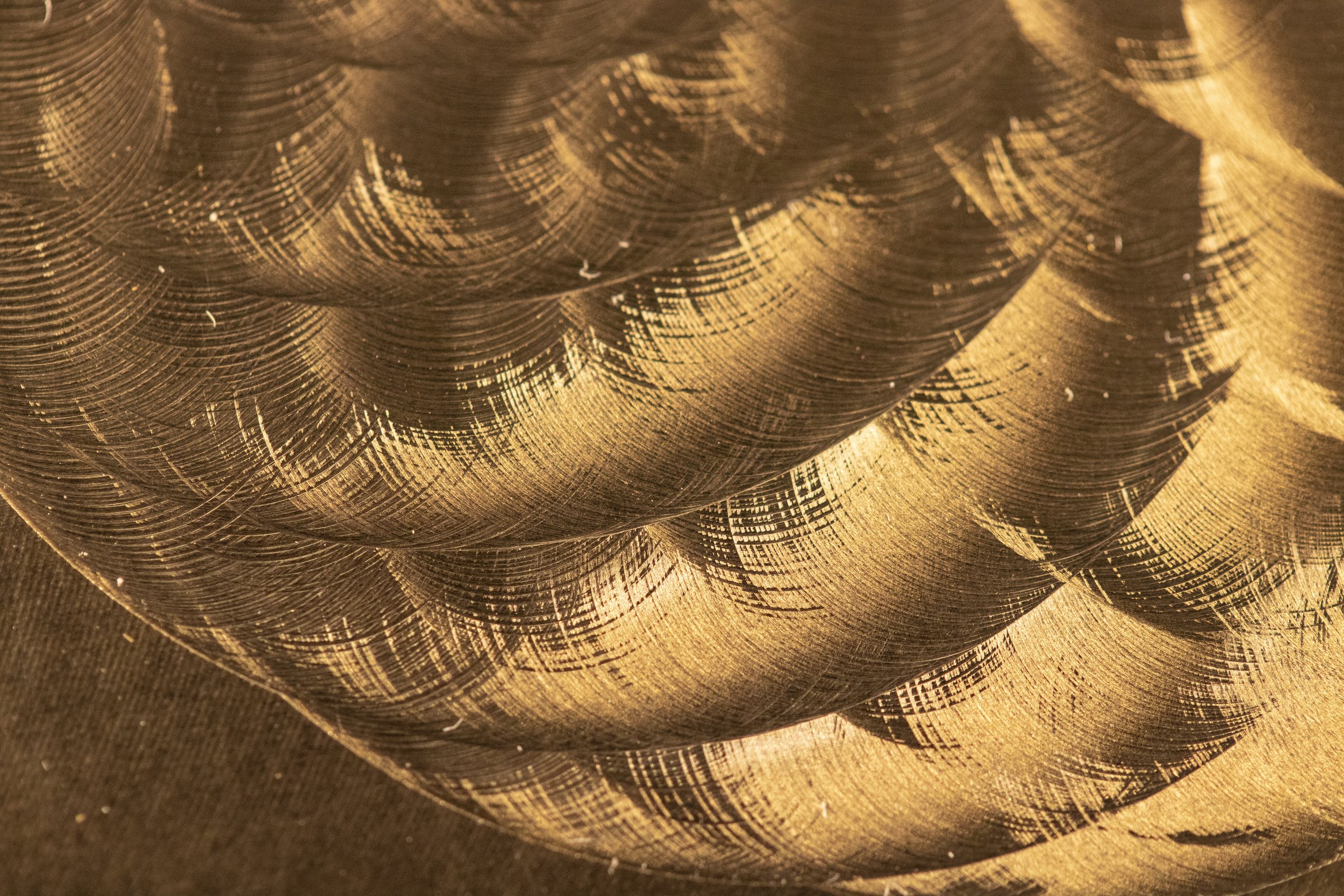

1/4” flat end mill machining brass 360.

CNC Spotlight

Have we mentioned we’re fans of brass 360? This alloy is a dream to machine on our Bantam Tools Desktop CNC Milling Machine and Bantam Tools Explorer™ CNC Milling Machine. Below are some of our tips and tricks we’ve picked up along the way—and brass eye candy.

Best bits: Use the biggest tool you possibly can, to allow for the fastest material removal and least chance of tool breakage. The easiest tools to use are 1/4”, 1/8", and 1/16" flat or ball end mills.

Hot tips: Brass may be similar to aluminum, but comparatively it is one of the less forgiving materials. It’s easy to break small tools with too high of a feed rate, inadequate fixturing, or simply having uneven material. While 1/4”, 1/8", and 1/16" end mills are very strong and make it easier to cut away a lot of material at once, any tool can be used to mill brass as long as the speeds and feeds are correct.

Beautiful Brass Projects

At Bantam Tools, we build desktop CNC machines with professional reliability and precision to support world changers and skill builders. For the latest Bantam Tools news, sign up for our newsletter. If you’re interested in adding a Bantam Tools machine to your workflow you can order directly from our online store or request a quote.